This slideshow requires JavaScript.

In my two recent blogs, I tried to explore the history behind my knowledge of painting. This voyage into the past, has made me discover great and ingenious artists and their school of thoughts and artistic movements.

My voyage started in Tuscany exploring the art movement called the Macchiaioli (see link for blog), then moving south in my native city Naples, I discovered the artists of (see link for blog), the Posillipo School (a seaside Naples’ neighborhood) which has now brought me here to this other art movement, to which I feel directly connected and influenced . The so called School of Resina (other name for the Roman city of Herculaneum, famous because destroyed at the same time of Pompeii by Mount Vesuvius)….So, who were they? What innovation they brought to the Italian art?

In 1863, by the initiative of a generation of brilliant artists, Herculaneum, then called Resina, a small town few miles south of Naples, on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius, gave birth to the eponymous school, also known as the “Republic of Portici“, addressing the theme of realism and the producer of extraordinarily beautiful works. Together with the School of Posillipo, the School of Resina is the highest representative of the nineteenth century Naples landscape paintings. Even today it’s still uncertain about who and how many artists have been part of this artistic movement, the arguments in this regard are conflicting: from those whom like the De Rinaldis, who would only reduce it to the big names and whom like Emilio Lavagnino who would also like to expand it to the artists closer to the Macchiaioli movement and to the “School of Posillipo” followers. For certainty we can say that four artists were the founders of this renowned School. Marco De Gregorio, the oldest and the only one native of the city of Resina, was joined later by Federico Rossano in 1858. Giuseppe De Nittis, from Puglia, who became the most renowned abroad, finally moving to Paris in 1867. Lastly, Adriano Cecioni, native of Tuscany. As also confirmed by Salvatore di Giacomo, the historical partnership merged in Resina in the decommissioned Royal Palace of Portici, the ancient Bourbon residence, surrounded by greenery, where Marco De Gregorio had his studio. Meeting place of the four and crossroad for the city of Resina and the city of Portici. From there left for outings in search of bucolic places, underbrush views, examples of the life and views to portray; from Vesuvius to the coast to go in the Gulf Islands.

“So every morning before dawn, I left the house and ran to look for my fellow painters, much older than me, Rossano and Marco De Gregorio. We started all together. I had no money and they were far from being rich, but they managed to rustle up a little money here and there, my meals were irregular and very frugal. But, I was used to this simple way of life. How many times have I just eaten bell peppers and salad! Good old days! With so much freedom, so much fresh air, so many races without end! And the sea, the vast sky and the vast horizons! Away the islands of Ischia and Procida; Sorrento and Castellammare in a rosy mist that gradually was dissolved by the sun … Sometimes, happy, standing under the sudden downpours. Because, believe me I feel the atmosphere, I know it; and I painted it many times. I know all the secrets of air and sky in their intimate nature. “

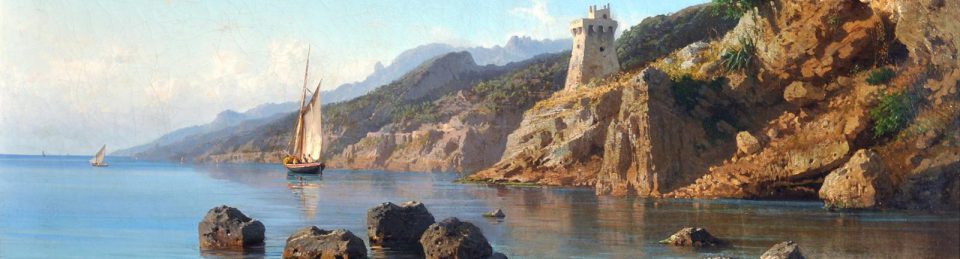

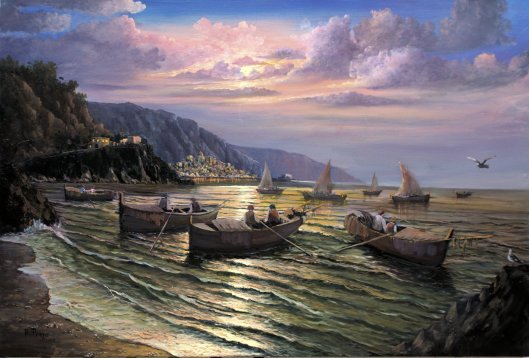

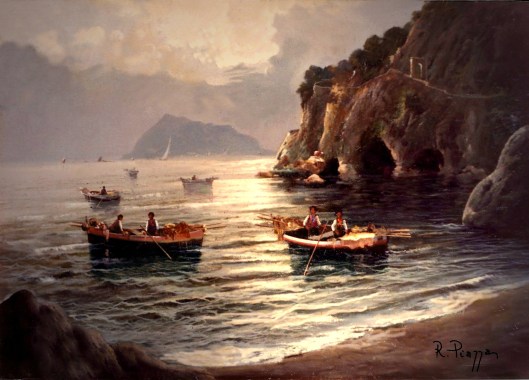

It is impressive the simplicity with which De Nittis describes those” happy days “, carefree days spent with his companions, enjoying the excursions around the city that transmitted a sense of freedom. It is extraordinary then the ability to reproduce on canvas and on board all temperate atmosphere of light and southern color. It is the play of light that characterizes the paintings of the School of Resina.

The gaze of a newcomer is immediately drawn to the light emanating from these paintings; those landscapes give off a glow that makes them unique. The paintings portray often clichés, destinations for outings and reflections where a surprisingly modern conception of light. Examples are: Rendezvous in the Forest of Portici, (Viareggio, Istituto Matteucci) of De Nittis, and the picture in the Forest of Portici of Marco De Gregorio, painted in 1875. The light filters through the trees and illuminates patches to the ground, creating a game of reflections and a warm color obtained from mixing with white lead. Adriano Cecioni spoke, with regard to the framework of De Gregorio, of “reasoning” of light, finding in it something no artist had ever done before: the insight to represent the filtered light from a canopy of leafy trees.

These were the signs, of the connection with the movement of the Macchiaioli, born in Florence, and based on this new concept of painting. The importance of the light in a painting, they also used to paint outdoors, the same characteristics that we find in the School of Resina. The movement from Tuscany was formed in Florence in 1856 in the small room of the Caffè Michelangelo where young artists were exchanging their ideas, often out by each school and academic rule. In Portici a few years later the same thing happened in the Caffè’ Simonetti where Marco De Gregorio, Giuseppe De Nittis, Adriano Cecioni, Federico Rossano and others of their followers became linked by an oath of brotherhood and an artistic program, initiated by long reflections made while they were sitting at those tables in the nineteenth century Portici.

The movement of Macchiaioli stated that the form does not exist but is created by the light, as a distinct color spots and superimposed on other spots of color, because light, striking objects is sent back to our eye as color. As common, the two artistic movements had their great exponent: Adriano Cecioni, that if for the School of Resina can be defined as a founder, for the Macchiaioli movement Diego Martinelli was certainly the major authority and academic, who dictated the basic rules of this newborn “style.”

The central characters for the subjects of their paintings are another element that links the two movements together. The recurring themes that inspired them are predominantly rural with common people that is almost always the poorest. The School of Resina restore the geographical and anthropological view of the lands of the South, a Southern Italy with its countryside, its inhabitants and its farmhouse until then not known by the rest of the country. Their paintings capture scenes of life they lived, immortalizing lower social class groups, giving them vitality and realism through the refined processing of vivid colors just as the characters that belong to it. A solid, intense color is found for example in the framework of Marco De Gregorio: Back on the field. Where paint takes on a particular form of realism rude and sincere. The residents, fishermen, farmers, sharecroppers, the ladies and the urchins are dressed with clothing that make their social role. The same realism we find in all the works of all the followers of the movement, as in the “Fair of Oxen at Capodichino” by Federico Rossano where natural elements such as tufts of grass, pebbles on the sides of the path and the clothes of the farmers together with shadow effects and light entering through the trees, are characteristic of the best School of Portici’s pictorial language.

The movement is dissolved in 1874, year of the final return of De Nittis in Paris. De Nittis thus becoming the official ambassador for the School of Resina in Paris, much appreciated by the militants of the Impressionist movement. The Impressionists had in common with the Neapolitan artists the rediscovery of landscape painting, the myth of the artist rebel to the conventions. They painted en plein air with a rapid technique which was used to complete the work in a few hours. Although they would lay their focus on landscapes at certain times of day with different light conditions, was the “light play” prerogative of the Resina’s School that they couldn’t ever achieve, which makes the difference and distinction between the two movements. The impressionists’ paintings as realistic and innovative, they were, despite the focus on landscapes at certain times of day with different lighting conditions hardly created the same optical effect, the play of light, which illuminates the Neapolitan paintings, filtering by trees, exploding on the walls of buildings or making magic outlines of people and things. that is the trademark of the School of Resina, which was renamed without any hesitation: The School of Light.